By Marie Ballarini

In France, museums are mainly public and almost all depend on state subsidies (private museums included). Faced with the stagnation of the latter, or even their substantial decline, many museums are turning to new sources of income in an effort to self-finance. At the request of their guardianship, it is becoming more and more common for museums to have to include in their funding projects a more or less significant share of self-funding, whatever the tool or tools chosen.

The recently published article focuses on a trend that seems new, crowdfunding, even though public subscription has existed for several centuries. The development of digital tools and specialized fundraising platforms is changing the current museum landscape; some museums seem attached to traditional subscription, others adopt these new models.

In order to identify if the choice of funding model depends on the museums’ strategy, an investigation was conducted to understand how and why museums use popular patronage and whether digital technology is changing the practices and habits of managers of museum institutions. What do managers expect from digital tools? Are digital tools perceived as communication tools or as real fundraising tools? In order to give an answer to these questions, the investigation alternates between quantitative data and interviews to describe current practices and envisage the short-term future of participatory sponsorship. With over 300 responses from museum managers to our questionnaire and around twenty interviews, our study is the first to investigate these issues on this scale.

Typology of museum and their relationship to crowdfunding

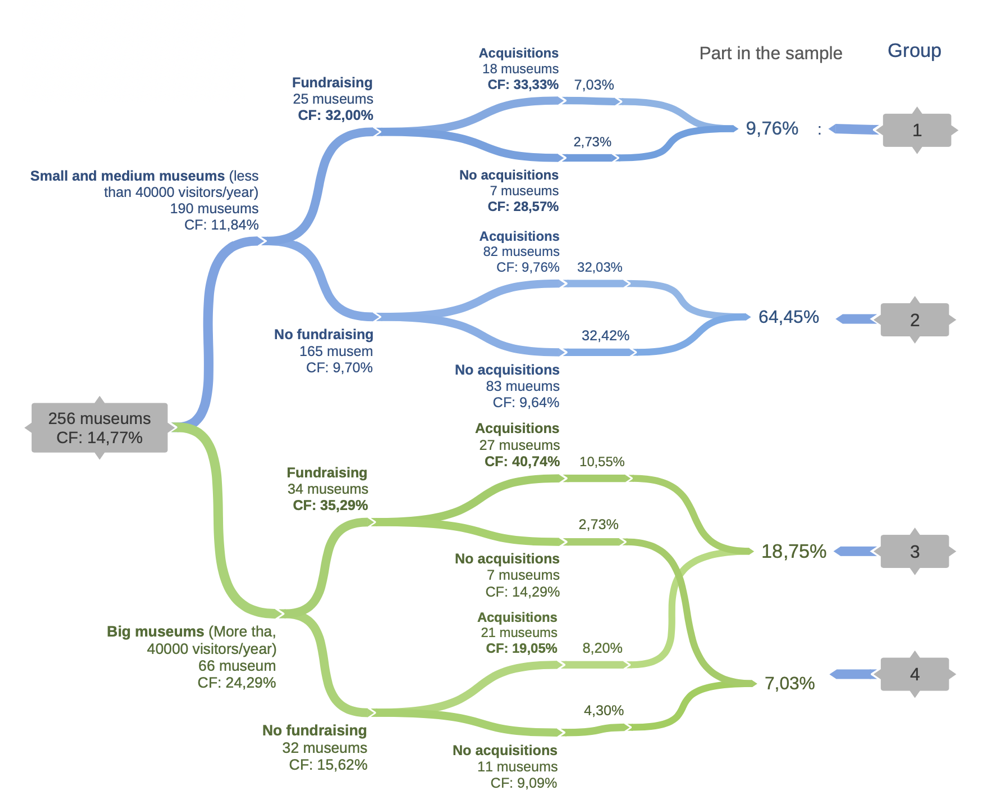

Before taking a closer look at the practices, the following typology presents museums according to 3 criteria that count for whether or not to run a crowdfunding campaign: the size, the benefit of patronage, and the decision to provide a budget for acquisition.

Figure 1. Tree structure of museums according to their size, their patronage practices and their acquisition policy

NB: “CF” indicates the share of museums in the group having carried out a crowdfunding campaign

This typology shows us that for 64.45% of museums, those which are the smallest and which do not benefit from patronage (group 2), the launching of a campaign is less frequent (less than 10% do so). However, it is not impossible. Despite everything, we see here a big difference with the small and medium-sized museums benefiting from patronage (group 1); much less numerous (9.76% of the sample), they are a third to launch campaigns. For these smaller museums (groups 1 and 2), the distinction between those who make acquisitions or not does not seem to be particularly relevant.

On the other hand, observation of major museums shows that if patronage also has a major impact in launching a campaign, an active acquisition policy doubles the chances that the museum has carried out a campaign in both cases. We note that if we simplify, a large museum that has made at least one acquisition in the last 24 months (group 3) has a 31.25% chance of having made crowdfunding, compared to 11.11% for those who did not buy anything.

Diversification of tools, both online and offline

The article first explores the different ways in which museums use crowdfunding, defined as a mechanism for collecting financial contributions – generally small amounts – from a large number of individuals – in order to finance a project.

After observing this type of funding offline and online, we have distinguished four types of initiatives.

Offline:

- The most traditional is the “subscription” model, where the museum publishes a call for donations, most often offline (but sometimes communicated online) for which the donor does not receive a reward (apart from the tax refund).

- The “patronage ticket” is another example of offline donation model. Visitors are invited to pay a little more for entry if they wish.

Online :

- Some use “external platforms”, which offer advice and online payment services in exchange for a commission;

- Others choose to develop “internal platforms” (on their own website), closer to the old subscription model.

These very different tools, however, raise the same questions from museums, whether in terms of administrative difficulties and legal implementation, or in terms of receiving these tools from the public. For the latter, from one tool to another, we find similar motivations for participation in the life of the museum and in the invisible missions of the museum (acquisition, conservation, restoration in particular), attachment to the place or to a project. These motivations are part of a common context of feeling of disengagement from local authorities or the State in general from cultural institutions.

The survey shows that 14.77% of the sample has launched at least one crowdfunding campaign in the past and more than 22% are planning or seriously considering it. These data allow us in the second part of the study to distinguish between the experience of museums that have already carried out a campaign and the representation that museums have of it that have not done so in order to be able to compare them.

If this work aims to analyse the dimensions of crowdfunding within museums, we must not forget that these innovations are part of a history, scientific projects, an established structure and in a complex interweaving of sources of income and complementary tools all having as final objectives the promotion of collections and their transmission to following generations.

Between funding and communication, a diversity of implications and results

Crowdfunding remains for the vast majority a very marginal means of funding, but more and more professionals see in these tools a new recurrent tool in their budget research increasingly turned towards private funding. For some museums, however, they appear to be a necessity to continue their scientific missions following significant reductions in support from the public authorities. This situation creates budgetary instability by letting some major missions rest on the philanthropic motivations of the population.

According to the perceptions of post-campaign museums, the use of the Internet to carry out a participatory patronage campaign makes it possible to reach a wider and younger audience, while subscription remains the tool of choice for the more traditional contributors to the museum. Some museums carry out campaigns regularly, sometimes by combining the tools from one project to another in order to reach a different audience, others launch ad hoc campaigns within a broader museum or territory policy based on global cultural events. In general, these tools allow to create a new link, to demonstrate an attachment to local heritage, to discover the museum as a scientific institution for conservation and not only as a place to visit.

The decision to engage in a campaign is considered and viewed as political, with elected officials having a say in these choices. They are sometimes reluctant vis-à-vis their constituents, sometimes very encouraging in approaches that are far from the traditional skills of a curator. Many local authorities are today asking their cultural services to increase their share of own resources, especially their sponsorship, often without the necessary legal and communication training that should accompany this development. Faced with increasingly smaller teams in many museums, the addition of news tasks such as research and the establishment of a loyalty policy for these patrons often rests on the curator when a specific development service does not exist (which is rarely the case).

About the author:

Marie Ballarini is associated to the Département de Médiation Culturelle, Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3.

This article is based on:

Ballarini, Marie (2020) ‘Musée et financements participatifs‘ in La Découverte | Réseaux. 2020/1(No 2019):203-240.

About the image:

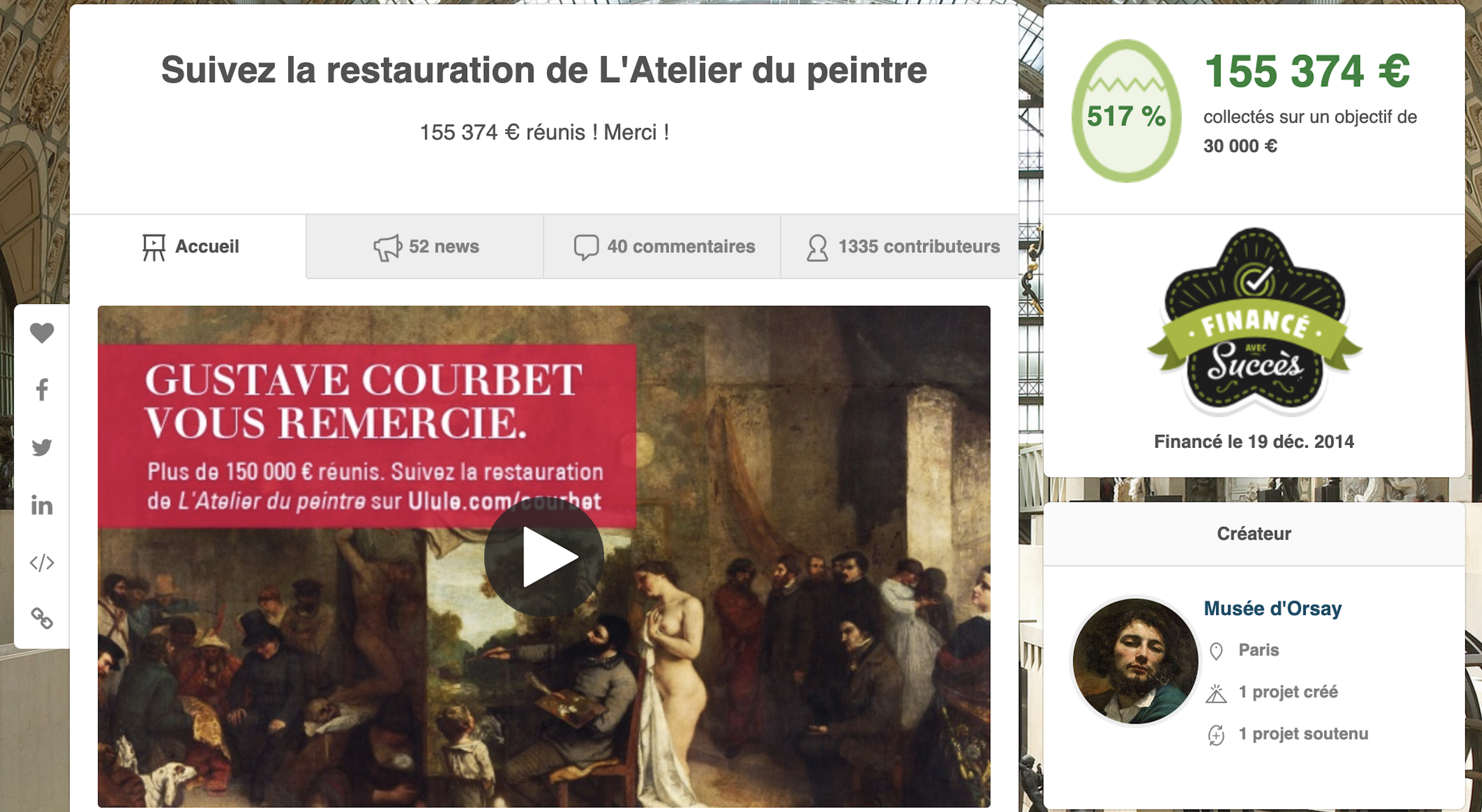

Screen shot of crowdsourcing campaign for the restoration of L’Atelier du peintre, by Gustave Courbet (1854-1855).