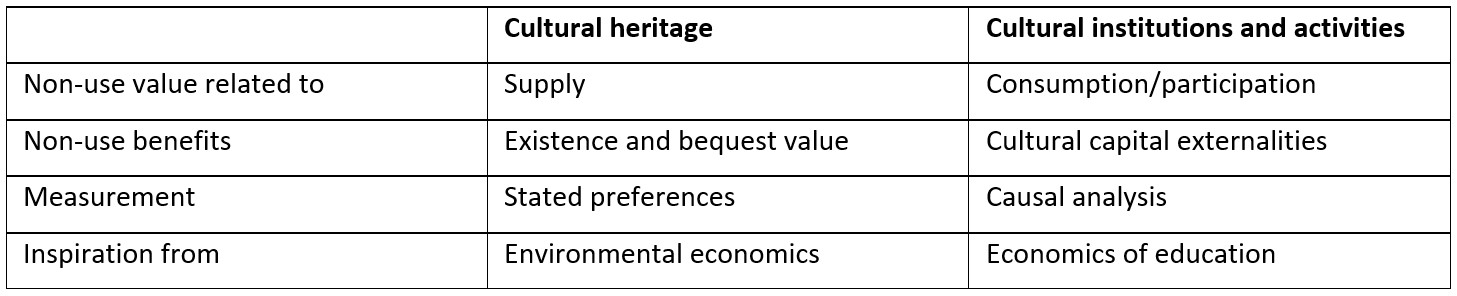

For many cultural institutions and activities, such as libraries, theatres, exhibitions and concerts, the non-use values are created when the good is consumed. These cultural capital externalities resemble human capital externalities for education. This stands in contrast to other types of cultural goods, like some cultural heritage goods, where the non-use values are related to the supply, not the consumption.

Since the early start of cultural economics as a research field in the 1960s, one of the main topics has been arguments related to public support for the arts and culture (Throsby, 1994). The common understanding is that the main arguments are based on externalities and non-use benefits, such as option value, bequest value, and existence value. These benefits escape the ordinary market.

Cultural economics has largely looked towards environmental economics and used non-market valuation techniques such as contingent valuation to estimate the total economic value of cultural goods (Noonan, 2003). The size of the estimated non-use values has been used as an argument for public support to the cultural good under valuation. These methods are well suited to the valuation of cultural heritage goods, where the non-use values are mostly related to the level of supply. In a recent article (Bille, 2024), I have agued that other methods are needed when the non-use values are mostly related to the level of consumption, and we need to differentiate between two different types of cultural goods in this regard.

When the non-use value is created when the good is consumed

For cultural institutions and activities such as theatres, libraries, exhibitions, and concerts, I have argued that the non-use value is produced, when the goods are consumed. Without the consumption by the users, no externalities are produced. For example, a library has little value without any users, and the externalities/non-use values are produced when the library is used.

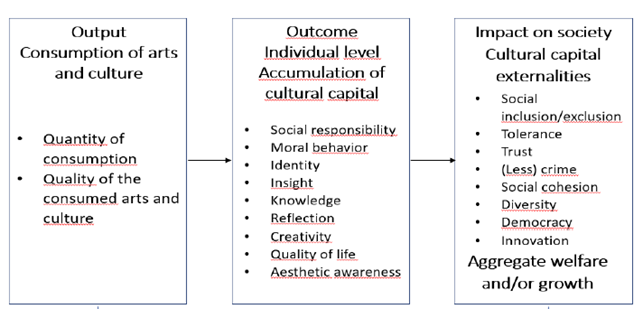

The assumption is that individuals taking part in cultural activities can be enlightened, connected, and empowered amongst other virtues that the arts generate. This can take the form of better understanding one-self and other people, changed perceptions, increase creativity, aesthetic understanding, social critique, better moral vision and so on. There exists an extended literature of qualitative research and case studies showing the effects on individuals from participating in the arts and culture (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2016; Carnwath and Brown, 2014). The expectation is that these effects on the individual will ultimately have a wider impact on the society level (social returns) in the form of e.g. democracy, diversity, innovation and so on (Figure 1), which in turn are also important for the aggregate welfare and/or economic growth.

The idea is that when private consumption of arts and culture is taking place, the individual will accumulate cultural capital. This accumulated cultural capital can impact other people (e.g. through changed behavior, future decisions, or interactions) and create externalities. In other words, many cultural institutions and activities are impure public goods, where a privately acquired activity jointly produces a public and a private good (drawing on a model by Cornes and Sandler, 1996).

Figure 1. Logic model: Possible impacts on individuals and society

Inspiration from economics of education and the concept of human capital externalities

For this type of cultural goods, I suggest that cultural economics should turn to find inspiration in the economics of education. The value of schooling can be divided into private returns and social returns (human capital externalities). Likewise, the value of cultural consumption can have a private and a public component, where I suggest labelling the public component cultural capital externalities. The size of these externalities is expected to increase with the level of consumption. Without the consumption by the users, no externalities are produced. While this is one of the most fundamental arguments for cultural policy, it has not yet been extensively studied within cultural economics. Table 1 shows some of the main differences between the two types of cultural goods.

Table 1. Different types of cultural goods

Cultural policy

In Denmark, 40% of the public support for arts and culture are spent on three types of cultural institutions, namely libraries, theatres and museums, and further about 25% is used to support public TV and radio (Bille, 2022). Similar priorities can be found in most Western countries. In other words, the majority of the public support is spent on cultural institutions, where most of the non-use value can be expected to be created when the output of these institutions is consumed. The main policy argument is the positive impact on the individuals using the cultural institutions (Bille, 2022), and the wider impacts this is expected to generate at the level of the society (the cultural capital externalities).

The logic model in Figure 1 comes of course with several important challenges. Firstly, it is important so consider the different the types, nature, or specific content of the culture being consumed. From a cultural policy perspective, the publicly supported consumption activities such as theatres, concerts, museums, and libraries are expected to provide some positive impacts. However, playing video games, watching TikTok, and viewing particular movies may have positive (or negative) impact as well. At the end of the day, it is an empirical question. Secondly, even though some evidence exists in the form of case studies and qualitative studies, the positive direction of the societal impact is an empirical question which needs to be explored further. Accumulation of cultural capital could potentially also lead to less tolerance, trust, social cohesion, diversity, innovation, etc. (Brook et al. 2020), and it would in addition be important to consider the skewness of distribution of cultural capital among the citizens. Finally, the measurement of the cultural capital externalities comes with huge challenges. We have made a first try to test the model in Denmark, using the variation across Danish municipalities in terms of aggregate theatre demand (Honoré and Bille, 2022).

Despite the challenges, I do recommend that research in cultural economics works with these questions and tries to find new ways to empirically investigate the existence and size of cultural capital externalities. These externalities are truly important for our understanding of the values of arts and culture and in terms of providing guidance for cultural policy decisions.

References

Bille, T. (2024): The values of cultural goods and cultural capital externalities: State of the art and future research prospects, Journal of Cultural Economics

Bille, T. (2022): Where do we stand today? An essay on cultural policy in Denmark, In: Sakarias Sokka (ed): Cultural policy in the Nordic Region, Kulturanalys Norden,

Brook, O., D. O’Brien and M. Taylor (2020): Culture is bad for you. Inequality in the cultural and creative industries, Manchester University press

Carnwath, J., and A. Brown (2014): Understanding the value and impacts of cultural experiences – a literature review, Arts Council England, London.

Cornes, R. and T. Sandler (1996): The theory of externalities, public goods and club goods, Cambridge University Press.

Crossick G. and P. Kaszynska (2016): Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture, Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK.

Honoré, S. and T. Bille (2022): Cultural capital externalities: Causal evidence from a Danish Ticket Scheme

for Theatres, working paper, Copenhagen Business School.

Noonan, D. S. (2003): Contingent valuation and cultural resources: a meta-analytic review of the literature, Journal of cultural economics, 27(3-4), s. 159-176.

Throsby, D. (1994): The production and consumption of the arts: A view of cultural economics, Journal of Economic literature, 32 (1), 1-29.

About this article

Bille, T. The values of cultural goods and cultural capital externalities: state of the art and future research prospects. J Cult Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-024-09503-3

About the author

Trine Bille is is a Professor at the Department of Business Humanities and Law, Copenhagen Business School.

About the image

Mx. Granger, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons