By Marco Serino, Daniela D’Ambrosio and Giancarlo Ragozini

In this study we contend that the co-production of theatre plays may have a critical impact on the ways producers position themselves in the theatrical field. Being involved in co-productions means taking part in the struggle for gaining rewards depending on the more or less advantageous partnerships one is able to exploit. Our study on a regional theatre system of Southern Italy reveals how such partnerships matter for producers to conquer dominant positions in the local theatre industry

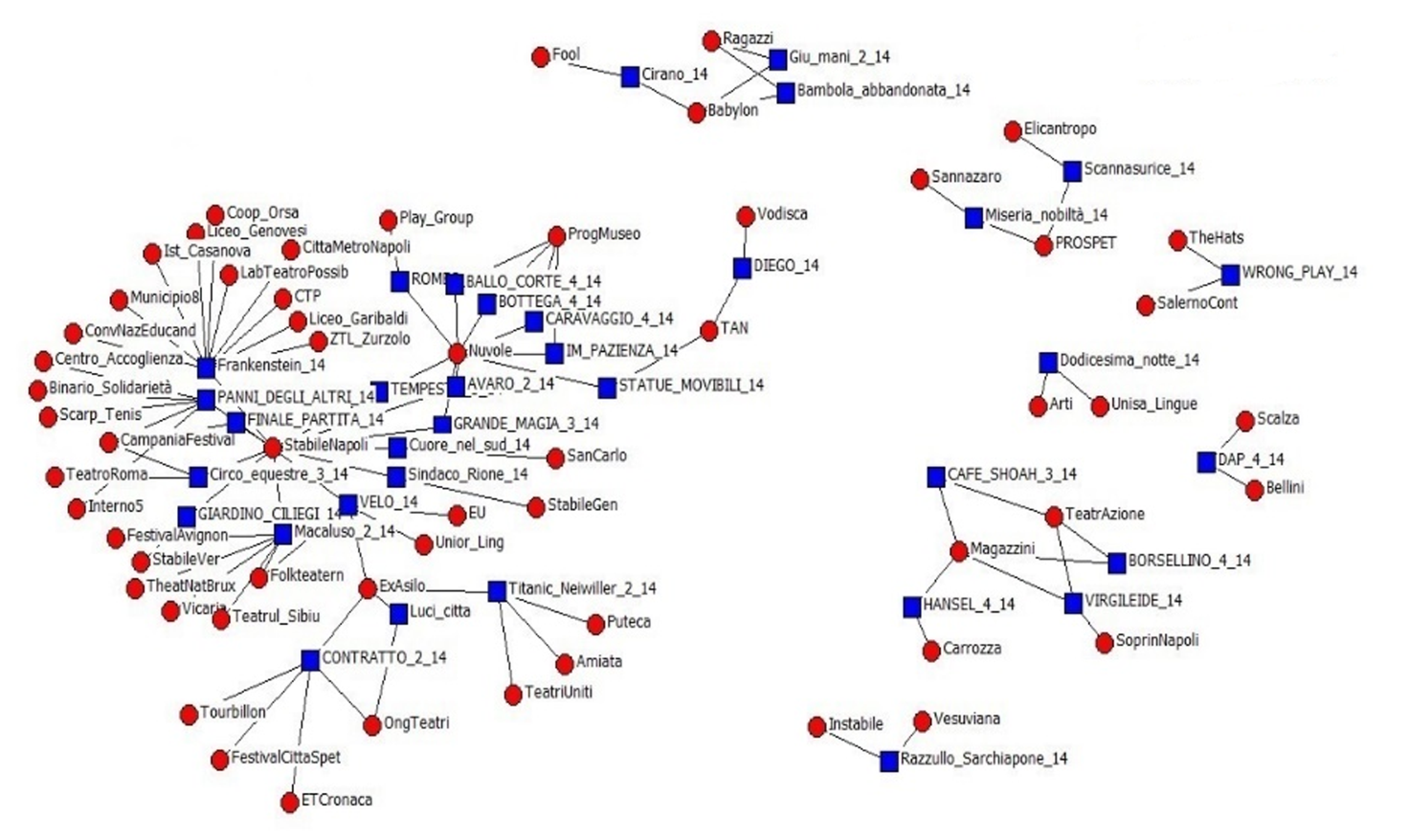

How do inter-organizational relations matter for producing art works? What are the implications of being involved in co-productions in the theatre sector? Do relations among companies constitute a field in the sense that what is at stake is how and with whom to take part in joint projects? These are some of the research questions of the present study. First of all, we conceive of the theatre industry as a field of cultural production, according to the well-known concept developed by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu[1]. The latter has focused on the analytical relation between categorical attributes defining the endowment of capital forms that artistic producers exploit in the field. However, actual interactions among producers do matter for understanding how they collaborate or compete with one another to gain success and symbolic recognition. This study aims at including such relations in a methodological framework able to depict the theatrical field of Italy’s Campania region. We have collected data on 157 co-productions staged in Campania over four theatre seasons (from 2011/2012 to 2014/2015) and jointly produced by 100 theatrical and non-theatrical organizations. In particular, we focus on the co-production as a form of company-production link generating a network of multiple partnerships, as in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Affiliation network of stage co-productions in Italy’s Campania region in the 2014/2015 season (red circle = company; blue square = co-production).

The methods we adopt are in part innovative in that we study this network of co-productions – namely an affiliation network[1] – through multidimensional data analysis[2]. Relations between companies and the co-productions they are involved in are treated as dummy variables (presence or absence of a tie) and as entries in a company-by-co-production matrix, along with the properties (categorical attributes) of both companies and co-productions. Such properties are indicators of capital forms. In this way, the theatrical field is seen as a space of relations and resources.

Our study is both explorative and confirmatory. The investigation of co-productions via multidimensional data analysis reveals the patterns of relations among producers involved in some sets of co-productions instead of others. This provides an indication of the partitions we are likely to obtain if we consider how theatre companies join each other in the same co-productions or find themselves relatively isolated from the leading projects. Then we model the networks of co-productions in line with our expectations regarding the patterns of relations in such networks. To this end, we opt for a network-analytic technique named blockmodeling (see our paper for the detailed methodology).

The different notions of capital in Bourdieu’s approach work well with our concerns. Theatre producers participate in stage co-productions in order to maximize their availability of economic capital, i.e. financial or material assets needed for staging productions. However, producers are also highly interested in being acknowledged as distinguished theatre companies in order to accrue their symbolic cultural capital. This is the reason why they try to be involved in highly valuable co-productions. Moreover, they can be interested in working with companies with similar artistic inclinations. We thus hypothesize that the field is segmented, as each company will join some companies instead of others insofar as those selective partnerships are more convenient or easier to be arranged. But we also hypothesize that some co-productions will be more attractive than others, so as to monopolize the field with an advantage for the companies that manage such partnerships. This will determine a hierarchy in the field.

Figure 2. The theatrical field in Italy’s Campania region (2011/2012 to 2014/2015).

The schema in Figure 2 represents in simplified form the theatrical field as it results from our multidimensional data analysis of both relations of co-production and companies and plays’ characteristics. Our findings show that the field is both segmented and hierarchized. Each square box in Figure 2 represents a network position, i.e. a partition of the relations of co-productions and a social position in the whole structure of the field, and comprises the companies that collaborate more or less frequently with each other in co-productions. Between these positions there are also relations that consist in dominance of one position over the other, or linkages characterized by equity in transactions and interactions (see the dashed arrows in the schema above).

One position, which we name the “Gatekeepers”, is shown on the left-hand side of the figure. It is made of two companies sharing a large amount of co-productions over the four-season span, i.e. a leading producing house and a foundation that acts as the former’s “sparring partner” in different projects. Both these institutions are publicly funded and acknowledged by the municipal, regional and national governments. This means they hold high portions of economic and symbolic cultural capital in the field. They are, too, in a position of power for being gatekeepers in terms of access to important theatrical projects, especially those hosted in a local theatre festival. In fact, the Gatekeepers also relate to the position of the “Guests” (which includes 91 organizations), whose members occasionally collaborate with (and economically depend from) the Gatekeepers. The latter’s productions are mainly focused on contemporary or classic plays – the dominant, mainstream theatrical culture – and participate with the Guests in other projects often concerned with experimental theatre. This enhances the symbolic recognition of the Gatekeepers and their dominant position in the field.

The “Insiders” are a producing house and a non-theatrical institution also characterized by frequent collaboration but with different aims and conditions: they share an interest in the production of educationally-driven plays (mainly devoted to the youth) and gain less funding than the Gatekeepers. Exactly opposite to the two positions of the Gatekeepers and the Insiders, the “Outsiders” are five companies with less economic and symbolic capital at their disposal and a more noticeable dependence upon the market: in fact, two of them usually stage entertaining pieces of comedy or musicals, while three of them are for the most part committed to producetheatre plays for young audiences. The members of this position have few linkages to the Gatekeepers that are mediated by some members of the Guests position. In addition, we also found relationships between the Insiders and the Guests.

We may conclude that the regional theatre system of Italy’s Campania, at least in its state at the time of our study, was markedly hierarchized and partly segmented. What is more, a large amount of co-productions were managed by two leading organizations that wielded symbolic authority in the field and also held economic power from which a large part of the producers in the region depended. As a policy implication, this meant giving to two organizations the power to control considerable financial resources – most of which derive from the EU – and also relational resources in the local theatrical field. Such resources might be differently managed in order to have both equity and efficiency in their allocation, and less constraints for companies to organize their activities.

[1] Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production. Cambridge: Polity Press.

[2] Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[3] D’Esposito, M. R., De Stefano, D., & Ragozini, G. (2014). On the use of Multiple Correspondence Analysis to visually explore affiliation networks. Social Networks, 38, 28-40; Ragozini, G., De Stefano, D., & D’Esposito, M. R. (2015). Multiple factor analysis for time-varying two-mode networks. Network Science, 3(1), 18-36.

The article is based on:

M. Serino, D. D’Ambrosio, G. Ragozini: Bridging social network analysis and field theory through multidimensional data analysis: The case of the theatrical field. Poetics, Vol. 62, June 2017, pp. 66-80.

About the authors:

Marco Serino, Department of Political Science, University of Naples Federico II, Via L. Rodinò 28, 80138 Naples, Italy.

Daniela D’Ambrosio, Department of Political Science, University of Naples Federico II, Via L. Rodinò 28, 80138 Naples, Italy.

Giancarlo Ragozini, Department of Political Science, University of Naples Federico II, Via L. Rodinò 28, 80138 Naples, Italy.

Image is based on:

https://www.greatbigcanvas.com/view/italy-campania-naples-san-carlo-theatre,2024320/