Drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption in Spain identifies and characterises the understudied group of sustainable fashion consumers, draws a comparison with the average Spanish consumer, and with this, defines the drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption. This research contributes to the attitude-behaviour gap literature.

The fashion industry has witnessed a significant rise in sustainability awareness, particularly in the aftermath of Bangladesh’s tragic Rana Plaza building collapse in 2013. However, despite the growing concern about sustainable fashion, there remains a disconnect with actual consumer behavior (Hassan, Shiu, & Shaw, 2016). This conundrum is commonly referred to as the attitude-behaviour gap or, more specifically, the fashion paradox (Black, 2008). Despite these issues, there is still limited research on the motivations driving consumers of sustainable fashion (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Hence, the purpose of Drivers and Barriers for Sustainable Fashion Consumption in Spain is to understand better why and how consumers engage in sustainable fashion consumption, in particular focusing on the context of Spain. The insights generated aim to further develop research as well as to guide practitioners and decision-makers in the field.

This study employs a mixed-method approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative part consisted of three focus groups with Spanish consumers: one focused on sustainable fashion consumers, and the other two dedicated to a broader range of consumers of different generations. For the quantitative part, we ran a survey that gathered 1,063 responses in Spain. The Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen, 1991) was used as the theoretical background to explore the differences in Environmental Concern (EC), Subjective Norm (SN), Personal Norm (PN), Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE), and Behavioral Intentions (BI) of sustainable versus average consumers.

Our research primarily focused on consumers in Spain and the unique characteristics of the Spanish fashion market. According to the 2019 Economic Report of the Fashion Sector in Spain, the fashion industry significantly contributes to the Spanish economy, constituting 2.8% of the GDP, employing 4.1% of the labor market, and accounting for 8.7% of exports (Modaes.es, Centro de Información Textil y de la Confección and Moddo, 2020). Notably, major international fashion groups, including Inditex, Mango, and Tendam, have established their headquarters and logistics facilities in the country, leading to the dominance of fast-fashion brands in the Spanish fashion market. The Eurostat Index of Prices for Clothing and Footwear (2019) reveals that the Spanish market boasts one of the lowest price indexes in Europe, being 8.6% cheaper than the EU27 average and ranking only above the UK, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. On the other hand, the Spanish sustainable fashion market is experiencing some growth in recent years, with brands like Ecoalf achieving international recognition, and an annual Circular Sustainable Fashion Week held in Madrid since February 2020. Interesting results come also from two surveys in 2020. The first one by IPSOS (2020) for the World Economic Forum highlighted that 76% of Spanish consumers have made lifestyle changes to combat climate change. The second by IBM (2020) indicated that 81% of respondents expressed concern about textile waste, with 68% considering sustainable fashion as important and 37% willing to pay between 1% and 5% more for sustainable fashion products.

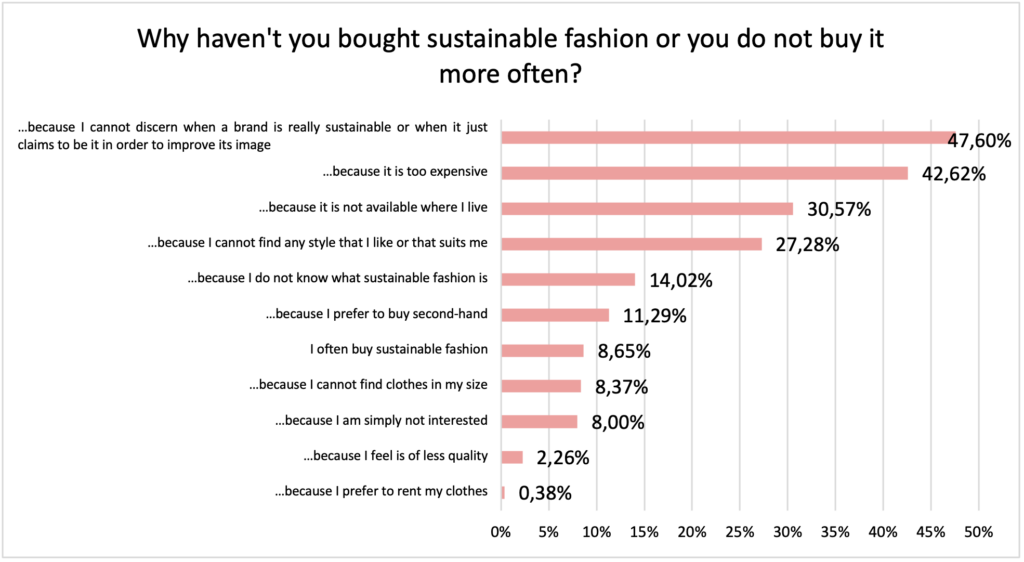

Let’s move to our results. Firstly, we examined consumers’ awareness of Sustainable Fashion (SF). Among the surveyed sample of 1,063 consumers, 90.03% of our respondents affirmed having heard of SF, while 73% claimed they could articulate their understanding of SF in their own words. Furthermore, 74.32% expressed interest in SF, and 39.51% reported having purchased at least one SF item. When respondents were asked about the reasons for not buying SF or not doing so more frequently, the most cited response – as depicted in Figure 1 – was, “Because I cannot discern when a brand is genuinely sustainable or when it merely claims to be in order to enhance its image” (47.60%). The second most cited answer was linked to higher prices – “because it is too expensive” (42.62%) – and the third one to availability in the geographical area of residency – “because it is not available where I live” (30.57%).

Notably, a mere 8.65% of the sample (92 consumers) regularly purchase SF. While prior studies had identified price, limited availability, and unappealing designs as barriers to SF consumption, our findings suggest that a lack of credibility and trust in fashion brands emerges as the primary obstacle towards SF consumption in Spain.

Figure 1. Frequency breakdown of the answers to the question “Why haven’t you bought sustainable fashion, or do you not buy it more often?” for the overall dataset (own elaboration)

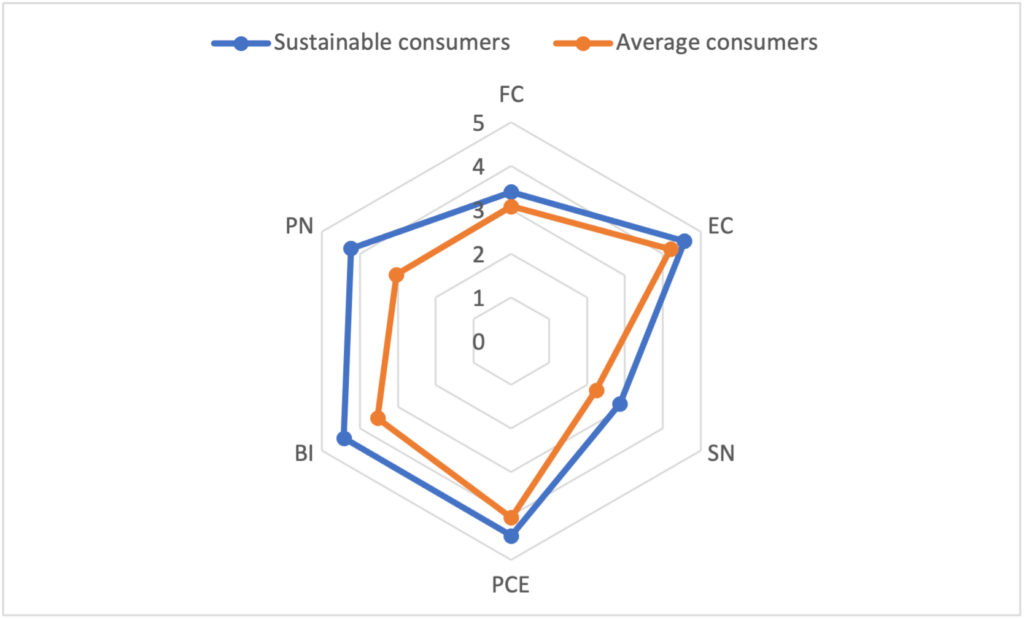

Furthermore, the study reveals that consumers who are more conscious of sustainability tend to rely less on purchasing brand-new items and prefer alternatives such as second-hand clothing or renting. Sustainable fashion consumers exhibit a higher degree of fashion consciousness (FC), environmental concern (EC), perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE), behavioral intention (BI), and a stronger personal (PN) and subjective norm (SN) compared to the average consumer as shown in Figure 2. In contrast, price remains a significant determining factor for the average consumer’s purchasing decisions.

Figure 2. Sustainable consumers vs. average consumers evaluation of the Theory of Reasoned Action model scales (own elaboration)

Our study highlights how crucial is for businesses to understand consumers’ purchasing behavior in specific contexts. In our study in Spain, the perception of ‘pressure’ to buy sustainably comes more from moral values than from the inner circle or society overall. This may indicate that Spain still lacks a strong “sustainable culture”. Therefore, individual moral values can be seen as an instrument of change. Additionally, the results indicate that it is essential for businesses to invest in palpable actions to be perceived as more transparent and trustworthy and combat greenwashing perceptions. There is, therefore, space for businesses and governments to nudge consumers towards more sustainable fashion choices.

About this article

Blas Riesgo, S., Lavanga, M., & Codina, M. (2023). Drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption in Spain: A comparison between sustainable and non-sustainable consumers. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 16(1), 1-13.

About the authors of the blog

Silvia Blas Riesgo is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, within the Department of Business Administration (IBW).

Mariangela Lavanga is an Associate Professor of Cultural Economics and Entrepreneurship at Erasmus University Rotterdam and the Academic Lead on Fashion Sustainability Transition at the Design Impact Transition (DIT).

Mónica Codina is an Associate Professor of Ethics and Deontology of Communication at the University of Navarra.

Julia de Koning is a junior researcher at Design Impact Transition (DIT), Erasmus University Rotterdam