By Hans Abbing

Respect for art is high, also among those who do not consume serious art, though subsidy cuts testify of a decreasing respect for the “serious arts”. In spite of cuts, the so-called “excellent art”, like the very costly performances of certain high-end opera companies, continues to receive much public support —support of which almost exclusively well-to-do people profit. The performances are sometimes innovative, but not more than most of the less costly performances.

The book The Changing Social Economy of Art, Are the Arts becoming Less exclusive? treats a broad range of topics covering changes in the perception of art over two centuries in all art forms. I discuss the social economy of art during what I call the period of serious art characterized by the high respect for serious art and rejection of commercialism. (In the book I explain why I use the term serious art and not high art or established art). This period runs from circa 1880 to 1980, but can also be observed during its prelude and its aftermath which lasts to the present day. Here I summarize general threads, some provocative theses and two of several novel approaches in the book.

As can be expected, an important thread in the book treats the “demand” for and the “supply” of exclusivity in the serious arts. One mechanisms of exclusion rests in the presence of an unattractive atmosphere during serious art performances. Along with the informalization in society from 1960 onwards, the stillness in the halls and museums have gradually contributed to less market demand for serious art performances and exhibitions. A change can be observed in the twentieth century where art worlds respond by offering a more informal setting. Classical music lags behind and this contributes to a continuing decrease in demand.

A second thread in the book is that of attention for technological developments and their incorporation in serious art and in popular art. Serious art is unwilling to use new techniques to lower cost in order to serve larger audiences, to lower prices and to decrease exclusivity. For example, classical music continues to attach much value to nominal authenticity and continues to use outdated production techniques. The resulting exclusivity is not unwelcome.

Another example can be found in technical reproduction of visual arts. Chromo-lithography was looked at with suspicion, considered a threat, looked down on, and considered to “give people false hope of becoming cultured.” Instead, artists offer exclusivity through limiting editions while maximizing income, advised by supposedly a-commercial galleries. It is significant that only after photographers started to limit their editions of art photos —currently down to three or two copies only— art photography become serious art.

This negative reaction towards technological developments in the serious art period is in high contrast with the period preceding it when developing and applying new production techniques lowered cost and led to artistic innovations. Popular music in the twentieth century is an example, among others, when the introduction of the electric guitar, the amplification of the human voice, and the digital processing and production of sound represented cost savings that were followed by major artistic innovation.

Exclusion in the serious arts period is not necessarily deliberate. It is a continuously reproduced art ethos that leads to visual artists limiting their editions, to stillness in concert halls, to an obsession with nominal authenticity and authorship, to the high value of symbolic membership in circles of art lovers, and so forth. (Membership circles can be very small like the circle of those who own art works that cost tenth of millions of dollars, but also very large, like the circle of what I call the “family of art”.) After 1980, gradual re-commercialization and somewhat lower subsidies start to contribute to renewal. This is partially because it is the only way for venues and art companies to survive; but more often it is because a new generation of artists and managers want art to be less exclusive.

Those familiar with art sociology and art economics will notice that there is much in the book that has been treated one way or another by others. However, what I do in the book is unusual: seemingly unrelated findings are connected with one another while using broad scientific perspectives. For instance, looking at the cost disease while relating it to more or less artistic innovation is not commonly done.

Some notions treated in the book are, as far as I know, novel. For instance, in order to separate serious art from popular art, inferior art, and other entertainment products, I use another definition of art worlds than Howard Becker. Moreover, I operationalize the notion of serious art (or “real art”) and artworks by their possible presence in “art buildings”. In the period of serious art, “real art” can in principal enter main art-buildings while other art cannot. —The buildings are the prestigious art museums, theatres and concert halls in which art is shown and performed. Any citizen knows the most prestigious art buildings and what and who belong there and what and who do not.

Another novel approach is my application of the notion of “enrichment” to art production and distribution. In the aesthetic capitalism of the twenty first century, enrichment in the arts is far more important than before. “Wrappings” or “extras” which are not part of the original artwork become more elaborate and are more emphasized. Artistic quality, authenticity, aura, and authorship are enriched. Marketeers play an important role in enrichment, and so do experts. For instance, art historians praise the most expensive artworks beyond comparison on television and serious music venues advertise immersive experiences rather than their exhibitions and concerts. Such enrichment contributes much to an ever-stronger winner-take-all mechanism, in the arts as well as in popular music.

Finally, the answer to the question in the sub-title of the book is predictable: “Are the arts becoming less exclusive? Yes…but….” The greater part of serious art is becoming more user-oriented, less serious, and less exclusive, but not for everybody. I argue that not all art is as interesting for everybody. Social groups can have different kinds of “own art”, or art that is meaningful for them. A problem is that there is little respect and money for the art of lower and marginalized social and ethnic groups, while artistic expression is particularly important for such groups. Either the chances of the latter’s art are very limited, or respect only emerges after the art has been appropriated and “civilized” by higher social groups.

In this blog I have emphasized provocative theses, yet much of the book is just educational and provides good-to-know information interesting for students, as well as funny illustrations interesting for artists and art-lovers. The book is available in all usual (online) shops. More information and a summary of the book can be found on the website which accompanies the book.

This article is based on:

Abbing, Hans (2019) The Changing Social Economy of Art, Are the Arts becoming Less exclusive? Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1007/978-3-030-21668-9

About the author:

Hans Abbing is Emeritus Professor at University of Amsterdam and teaches at Erasmus University.

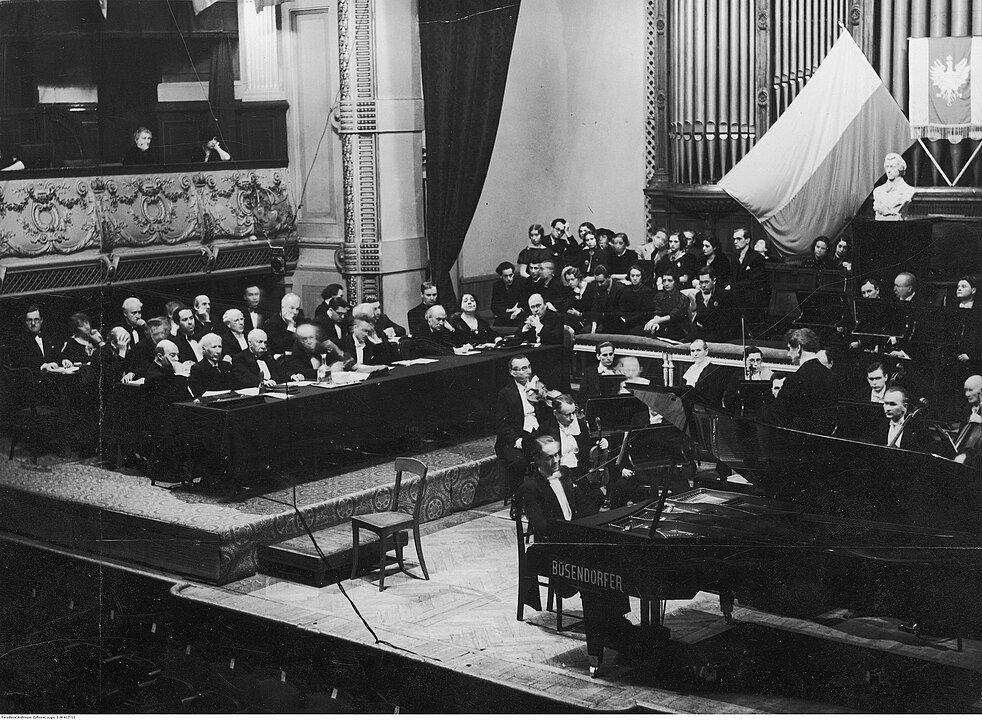

Image:

Book cover (detail)