By Enrico Bertacchini and Francesco Puletti

From the ashes of the creative city paradigm, there is a growing awareness of the urban creative economy as a complex adaptive system of intertwined actors and institutions. Yet, especially in the European context, little attention has been given to understanding informal and alternative art spaces and venues that contribute to the vibrancy of the urban cultural scene.

Alternative cultural production can be defined as a set of informal and emergent artistic practices, mainly in small- to medium-sized spaces that engage in cultural production through various activities and projects appealing to both professional and general audiences. These initiatives tend to be alternative to commercial and more institutionalized cultural circuits in the search for new artistic frontiers or new ways of using artistic practices in relation to the local context and the social fabric.

A limited but growing number of scholars have addressed this phenomenon according to different analytical perspectives and labeled it in several ways, such as independent creative subcultures, grassroots creative production, spaces of vernacular creativity, off-culture venues, scene-based cultural production and community-based arts institutions.

In our study, we conceptualize distinct types of alternative cultural spaces based on two strategies through which they seek to achieve an alternative status from the mainstream arts and cultural institutions.

Specialized art spaces are organizations focused on experimental production and tie their alternativeness to the design of an inherently innovative and avant-gardist cultural offer that aims to be independent of institutionalized artistic canons. Legitimacy within the arts field is built through an organized and planned relationship with more established and renowned cultural institutions as a strategy to pursue the recognition of talents and ideas involved in cultural production. From the organizational point of view, specialized art spaces often provide goods and services commercially as an alternative funding mechanism to sustain their art-related activities. Such strategy intersects with a higher degree of entrepreneurialism and professionalism in the art field sustained by the work of mavericks and innovators.

Cultural aggregators tend to be oriented toward a more diversified cultural offer, creating opportunities for the engagement and interaction of diverse audiences and groups. The primary source of cultural recognition is connected to the achievement of community-building goals for specific constituencies, particularly at the neighborhood level. Therefore, cultural aggregators have a primary role in ‘voicing’ underrepresented communities and enhancing their visibility. Non-market mechanisms, such as public grants, self-financing, and gift-economy sources, are central to the economic sustainability of this type of organization. Indeed, since cultural aggregators carry out a more naive, folk, and grassroots form of cultural production, they are less like to search for sustainability in market-based and entrepreneurial models. Cultural aggregators also tend to rely on alternative exchange networks where the actors are consciously motivated to construct circuits of value independent of mainstream institutions or processes, either as a form of entrepreneurial necessity or as political contestation to the market dynamics of the cultural economy.

Insights from Turin’s alternative cultural production

Applying such a distinction, we have investigated the organizational, spatial, and relational structure of more than 50 art spaces in Turin, Italy, an industrial city that has experienced a radical urban transformation based on culture-led development strategies.

Our findings suggest that the two types of organizations coexist within the alternative cultural landscape. However, the differences in their mission and operation reflect in their organizational structure, locational choices, and attitudes in establishing collaborative ties within the network and relationship with the neighborhood.

While both specialized art spaces and cultural aggregators share similarities in their activity, one of the main differences concerns the size of non-permanent job positions, with cultural aggregators relying more on temporary and voluntary work. This difference possibly underlies distinct ways specialized art centers and cultural aggregators build social capital, either bonding artists’ relationships within the cultural field or bridging it with the broader audience community

Turin’s cultural aggregators are also more likely than specialized art centers to act as recipients or brokers in the network of collaborations. However, sharing similar artistic domains remains relevant in shaping connections across the two types of organizations. From a spatial perspective, all the art spaces have clustered in peripheral areas of the city. However, the analysis also points out possible different spatial dynamics for the two types of organizations. Over twenty years, specialized art centers have served as pioneers in settling in areas of real estate transformation, while cultural aggregators have followed. This dynamic is also reflected in interviewees about locational choice.

While proximity to other art spaces, the cultural atmosphere, and the residential composition of the neighborhood has often been highlighted as important by cultural aggregators, these factors are considered by specialized art centers as secondary to the accessibility, functionality and affordability of the space.

The article is based on:

Bertacchini, E. E., Pazzola, G., & Puletti, F. (2022). Urban alternative cultural production in Turin: An ecological community approach. European Urban and Regional Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764221076999

About the authors:

Enrico Bertacchini is Associate Professor at Department of Economics and Statistics “Cognetti de Martiis”, University of Torino, Italy.

Francesco Puletti is a PhD research fellow at DIST – Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning, University of Turin and Polytechnic of Turin, Italy.

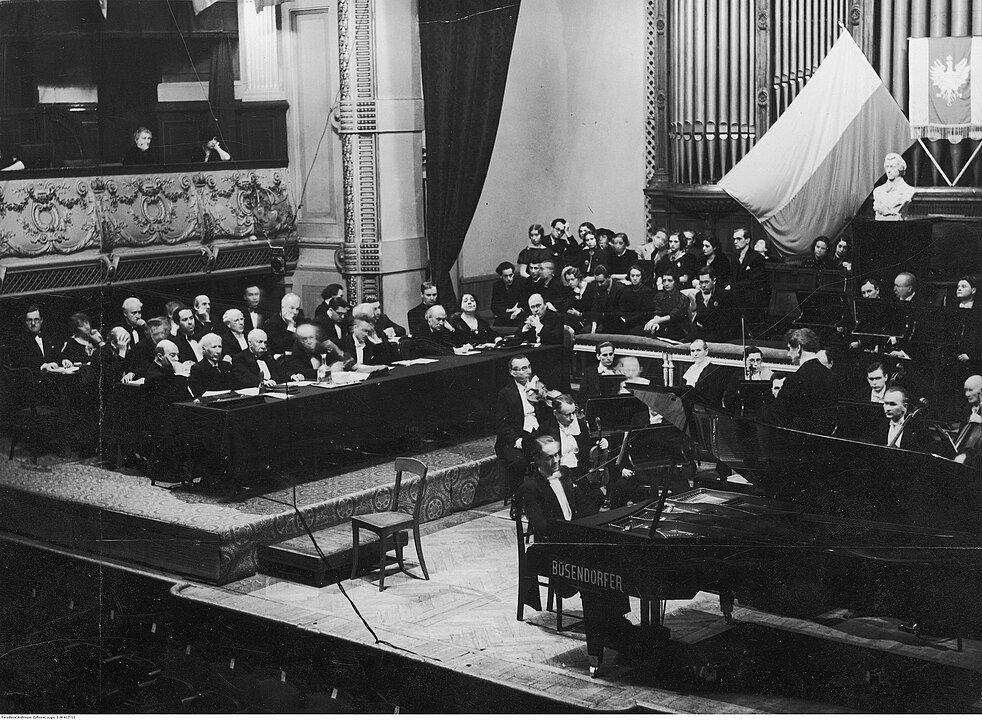

About the image:

SOLUZIONI festival @ Stasis Lab, by Marianna Lembo & Matteo Pinna