By Sabrina Pedrini and Pier Luigi Sacco

The creative industries have been regarded, for many years, as the soul of urban development. Among these, the music industry is particularly vibrant in Italy. In this study, we show how the city of Bologna has developed a vital cultural “humus” that characterised the brand of the city itself, thanks to particular socio-economic conditions. However, the engineering of cultural policies adopted since the 1990s is leading to greater individualism and a loss of cohesion even within the musical community, losing the identity that has made the “city’s fortune”.

The music industry has been studied from different disciplinary fields that found the existence of a relationship between music communities and the urban contexts in which they are embedded (see Pedrini et al., 2021).

Many factors determine the attractiveness and vibrancy of a given urban milieu that are necessary support to the creation of a local scene. The virtual character of a music scene reveals a form of spatiality that defines itself in a placeless: virtual space that maintains its social exchange and shares idiosyncratic cultural coding and articulating situated grammar. Nevertheless, there is no simple formula that can predict whether or not a specific city will become (or stay) culturally vibrant. Eventually, the reasons behind successes and failures in this regard may remain relatively elusive.

The Italian city of Bologna provides an exciting example of a local music scene from 1978–1992, where it acquired prominence at the national level in terms of music and authorship production. Bologna was (and still is) a medium-sized city whose local specialisation model was not significantly centred upon cultural production and cultural industry. At the same time, its geographical proximity to major cultural centres like Milan or Florence has traditionally been an obstacle to its national positioning as a significant cultural hub. The peculiarity of Bologna was mainly linked to the dense relational structure between small and active musicians communities, with specific distinctive traits. Favourable political and social conditions nourished a juvenile, inclusive, multi-ethnic environment, establishing the city as a recognised capital of quality of life and easy living. Bologna was also one of the key hubs of Italy’s alternative culture, having been one of the main theatres of the 1977 student protests (also due to the presence of one of Italy’s largest universities). This peculiar socio-cultural environment set the stage for an urban laboratory of vital, grassroots cultural experimentation supported by noninvasive public policies.

From the 1990s, a new cycle of urban regeneration policies started, focusing on the inner-city centre, gradually powering down grassroots community ties, and inducing increasing re-urbanisation and social control of the urban space (Bergamaschi et al., 2014; Buzar et al., 2007). The ambition informed the new cycle of engineering the city’s cultural vibrancy through a form of top-down institutional control. This brought to the downsizing of some of Bologna’s most dynamic and independent cultural spaces to curb their antagonist urban culture social hubs role (Felicori, 2001), pursuing the ambition of “absorbing” creative strength (see Calafati, 2015), to reenact it in more domesticated, institutionally compliant forms (Aiello, 2011). However, artificially re-creating the conditions for cultural vibrancy is often a self-defeating strategy. In the case of Bologna, the city’s profile in the national music scene has been gradually eroded ever since, paving the way to a long-term cycle of relative cultural stagnation. The “cultural engineering” effort undertaken in the nineties continued in the next decade and culminated with Bologna’s designation as one of the eight European Capitals of Culture of 2000. However, this retrospectively turned out to be the city’s swan song as a primary national cultural stage. The legacy of the EU Capital of Culture has been controversial in turn.

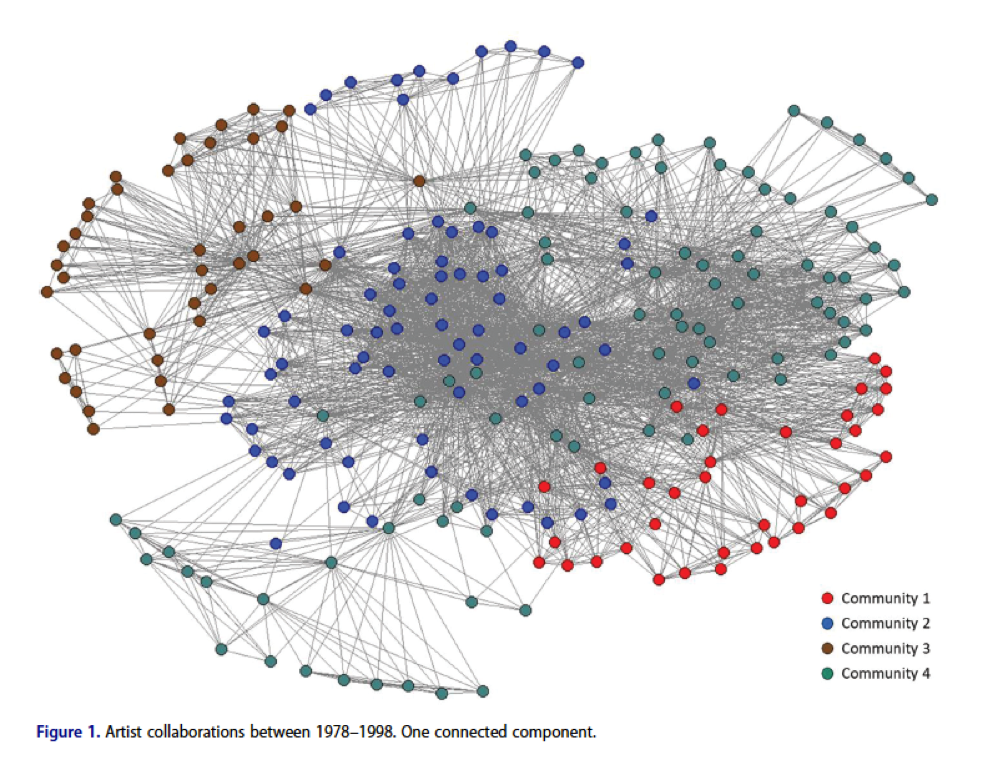

Social Network Analysis (SNA) methods are specially indicated to analyse a case study like this. We apply the Newman Community Detection algorithm from SNA’s essential analytical tools and a preliminary core-periphery approach (Newman, 2006). Using SNA, we show how such relational networks have shaped Bologna’s cultural landscape during the analysis period.

In Fig. 1 (elaborated by Raffaele Corrado and Sabrina Pedrini), we can see the high level of social cohesion within this community and four different thematic groups, strictly linked regardless of the different genres of music on offer. Such a high level of collaboration is unmatched by any other cultural and environmental context and was destined to decline in the following decades, notwithstanding the cultural policies introduced, which prompted a higher level of individualism even within the artists.

The eco-systemic nature of cultural and creative production implies continuous contamination between cultural sectors and between the latter and more traditional commercial industries. The period studied is dynamic and is not matched by commercial success, which will come later but was essential humus for the future economic success in a sector very sensitive to subtle issues such as authenticity and meaningfulness.

It would be interesting to compare the Bologna case with other musical scenes in European or non-European mid-sized cities or even with the cultural scenes of mid-sized cities centred around different creative fields. From a comparison among such cases, we could learn important lessons about the onset, resilience, and sustainability of cultural scenes and the critical factors that lead to their eventual demise. These are topics that policymakers should take seriously in a historical moment in which an increasing number of cities is launching ambitious plans of creative development or revitalisation.

About the publication:

Pedrini S. Corrado R., Sacco P.L., (2021), The power of local networking: Bologna’s music scene as a creative community, 1978–1992, Journal of Urban Affairs. DOI: 10.1080/07352166.2020.1863817

About the authors:

Sabrina Pedrini is Adjunct Professor of Cultural Economics at the Department of Management of the University of Bologna and Adjunct Professor at IULM University and Catholic University of Milan.

Pier Luigi Sacco is Full Professor of Cultural Economics at IULM University Milan, Senior Researcher at the metaLAB at Harvard, and at the Bruno Kessler Foundation; and Senior Adviser at the OECD.

About the image:

Lucio Dalla, Gianni Motandi Ron in 1979. Fragment.