By Emmanuel Coblence, Cyrille Sardais and Josée Lortie

What do orchestra conductors actually do? How can arts leadership articulate both “discipline” and “creativity”? Through the use of ethnographic data and interviews, this study suggests that the orchestra conductor’s leadership relies on disciplinary devices to gain strength and freedom, while avoiding the trap of “over-leading”.

For decades, the metaphor of the orchestra conductor has been used in leadership studies, including work by some of the most renowned management gurus, such as Peter Drucker or Henry Mintzberg. For instance, conductors are said to have learned how to lead a large group of autonomous experts virtually by themselves, an issue faced today by many organizations which are based on the highly specialized knowledge of their professional staff and the absence of intermediate hierarchical levels. Mobilizing the extensive experience and know-how of orchestra conductors is thus a relevant area of management research and practice. In his 2009 TED Conference, famous conductor Itay Talgam provided sources of inspiration to business leaders on “How to lead like great conductors”: his brilliant speech has been viewed more than 3.5 million times today.

However, there is surprisingly few studies of conductors’ leadership that build on empirically grounded elements and on a full understanding of the organizational and human mechanisms of conducting. In our 2019 article published in the International Journal of Arts Management, we adopt an ethnographic perspective to show how the conductor’s leadership is deeply embedded in the “disciplinary device” that the orchestra and its organization constitute.

The term “discipline” was first suggested by French philosopher Michel Foucault in his famous book Discipline and Punish to characterize the organizational and material mechanisms of certain institutions – such as prisons, hospitals, military barracks and boarding schools. According to Foucault, these organizations function by “disciplining” individuals. Bentham’s “panopticon” constitutes an extreme form of discipline, in which a supervisor may see everything without being seen.

While it constitutes an increasingly important theoretical framework in management research, Foucault’s work has barely penetrated the field of arts and cultural management. This is understandable, as “discipline” may appear at odds with creative organizations such as a symphonic orchestra. Yet, our field research on orchestras and their conductors suggest that much on artistic and cultural organizations can still be learned from the Foucauldian approach. To explore this perspective, we interviewed 13 conductors (from novice to world-renowned) from one Canadian province and carried out over 70 hours of ethnographic observation of rehearsals concentrated around four orchestras.

Our research highlights three main results:

- First, we conceive the symphony orchestra as a disciplinary organization. Spatial settings, body positions, repeated exercises and rehearsals, and organizational routines act as mechanisms of discipline. Yet, these mechanisms are not at the service of confinement or incarceration, but rather of artistic and creative accomplishment. Discipline allows creative collectives to do their work; it generates freedom. We find that the leader’s presence and interventionism are not always necessary. The leader of a creative organization must be “parsimonious”, i.e. let members of the collective express themselves, thus avoiding the trap of “over-leading.”

- Second, we call the romantic vision of creation into question. While it is commonly agreed that there is an artificial separation between administrative and creative activities, our study underlines the link between discipline and creation, and thus narrows the gap between artistic and managerial activities. In practice, it appears that doing away with constraints, norms or any other disciplinary device is the last thing a leader should do if the goal is to make the organization more creative.

- Finally, our research suggests that the essential leadership work and skills of the conductor are not so much to enforce discipline (which is largely independent of his or her actions) as to detect the key moments in which he or she must free him/herself from it – that is, when the interpretation of the piece requires it. As a conductor explained us: “The conductor must act in such a way that the musician in the orchestra feels that he is being directed effectively while at the same time the entire orchestra is free”.

We believe that these observations and managerial recommendation may be relevant in many contexts or sectors where innovation and creativity are key strategic resources such as haute cuisine, architecture, video game, design, or technology.

About the authors:

Cyrille Sardais is associate professor and Pierre-Péladeau Chair in Leadership at HEC Montréal.

Josée Lortie is partner in the Pierre-Péladeau Chair in Leadership at HEC Montréal.

Emmanuel Coblence is associate professor at ISG Paris.

The article is based on:

Sardais, Cyrille, Josée Lortie, and Emmanuel Coblence. “Inside the ‘Panacousticon’: How Orchestra Conductors Play With Discipline to Produce Art.” International Journal of Arts Management, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2019).

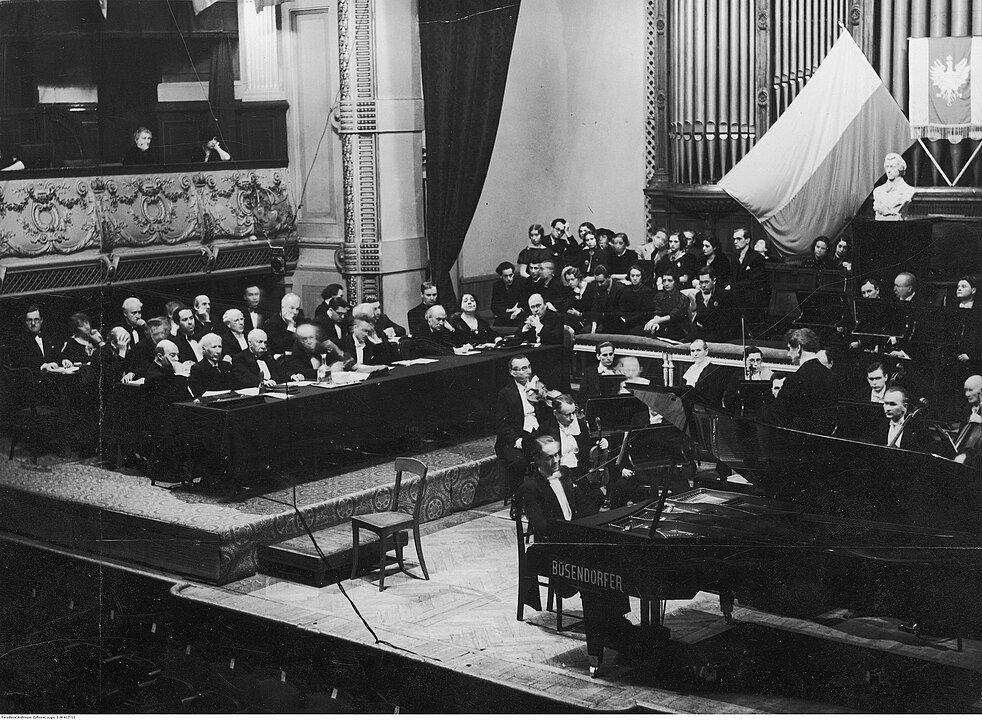

About the image:

“Conductor in full swing” by Rob van Hilten is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0