By Redaction

Maybe we’ve been thinking about science all wrong. In the old model, knowledge was privately produced, then ‘communicated’ to make it a public good. Journals did the communicating. But a better model is to think of this whole process as a club of both producers and consumers together.

Over the past year or so a motely group of us Australians – we collectively publish under the name Redaction – have been working on a new way of understanding scholarly publishing. The old private proprietary model of wealthy publishers, desperate libraries and overworked editors seems to be well and truly broken. But the open access model for journals, which was to fix all of these problems by making journals radically public, is not really doing as well as everyone had hoped. Private didn’t work, so we are trying public, and discovering that there are still difficulties.

What else is there? In economics, there are two more possibilities beyond private goods and public goods: common pool resources, and club goods. It occurred to us that academic communities are extremely clubbish and academics naturally form into clubs that are variously called departments, schools, fields, sub-disciplines and universities. Their whole social and communicative structure of conferences, seminars, and journals (!) are clubs. Indeed, as a groupish animal, they become extremely distressed when isolated from their clubs.

Our working paper is called ‘A Journal is a Club: A New Economic Model for Scholarly Publishing’.

Cameron Neylon has written about the origin of the idea here, which itself arose from a book that Hartley and Potts recently wrote called Cultural Science, which was all about the ‘nature of culture’ as group formation, which they define with the concept of a deme. They were trying to reinvent the humanities using evolutionary economics. The ‘Journal is a Club’ idea is all about reinventing scholarly publishing using a different part of economics, namely club theory that was developed by the Nobel Prize winning economist James Buchanan.

The problem with the standard economic models of publishing – both the private and public goods versions – is that they don’t capture the human-group-reputation aspects of scientific and scholarly production. But club theory does, which is why it gives us insight into understanding the role played, not only by journals, but also libraries and other institutions of both the production and communication of knowledge.

Indeed, this insight that research groups are clubs hints at a larger claim: that knowledge-production and knowledge-growth require culture-made groups (Buchanan clubs). This in turn suggests a whole new approach to Open Access policy, which should be directed to enabling the formation of new groups and to developing coordination among groups rather than mandating individualistic open information.

A model of scholarly publishing as a club good starts by focusing on the way in which scholarly output is produced and consumed. Producers of knowledge seek to interact with other producers, of whom they will also be consumers of a fuzzy set of that same knowledge. That the producers are also the consumers is a key insight into the clubbiness of knowledge.

Knowledge clubs are evolving communities with self-chosen governance structures through which scholars interact, in part through the mechanism of publishing, and a dynamic self-constituting membership through entry by new scholars and exit as scholars leave. The arguments of philosophers of science Karl Popper and Thomas Kuhn on the nature and structure of scientific revolutions reinforce this club-like aspect of the dynamics of science.

Members of a knowledge club can in the language of economists ‘confer externalities on each other’ in the form of readership, critique and understanding that is set against the congestion costs imposed. The crowding costs are access to those same journal slots, which increases the larger the club.

We think this idea might have implications beyond rethinking the nature of scholarly publications—i.e. fixing journals—and also extend to how the role of some of the larger cultural institutions of science and scholarship, notably libraries, museums and galleries, is understood. These institutions have also tended to maintain a private-public line of separation around knowledge – with the producers here and the consumers over there. And at the same time, they seem to be in perpetual business model crisis. We wonder if the same diagnosis might not apply.

In terms of journals, the implications of club theory are about where investment is directed. Universities currently pay large sums of public money to private journals. Directing that money to knowledge clubs, whose role it is to maintain the infrastructures that are required to keep the club active – including journals – makes sense if we start from club theory.

A more radical implication is that knowledge clubs become spaces for experimental self-governance. Club theory requires that we pay closer attention to the incentives to participate, including in tasks such as journal editing and refereeing that are not acknowledged in standard academic metrics. New technologies, and the organisational structures associated with them, might enable more efficient and effective systems.

One next step, which we have begun to explore, is how emerging platforms, including Ethereum, might be used for scholarly journal processes. Those that publish, referee or edit the journal could receive tokens for their labour, which could provide a transparent means of assigning reputational status, enabling those within the club to earn voting rights through their efforts within a Distributed Autonomous Organisation governance structure. Our paper provides some preliminary thoughts on how this might unfold, laying the groundwork for future experiments.

This article is based on:

Potts, Jason and Hartley, John and Montgomery, Lucy and Neylon, Cameron and Rennie, Ellie, “A Journal is a Club: A New Economic Model for Scholarly Publishing’” (April 12, 2016). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2763975.

Author information:

Redaction is made by:

Jason Potts is Professor of Economics at the RMIT University.

John Hartley is Distinguished Professor at the John Curtin University.

Lucy Montgomery is Associate Professor at Curtin University’s Centre for Culture and Technology.

Cameron Neylon is Professor of Research Communication at Curtin University’s Centre for Culture and Technology.

Ellie Rennie is Deputy Director of the Swinburne Institute for Social Research.

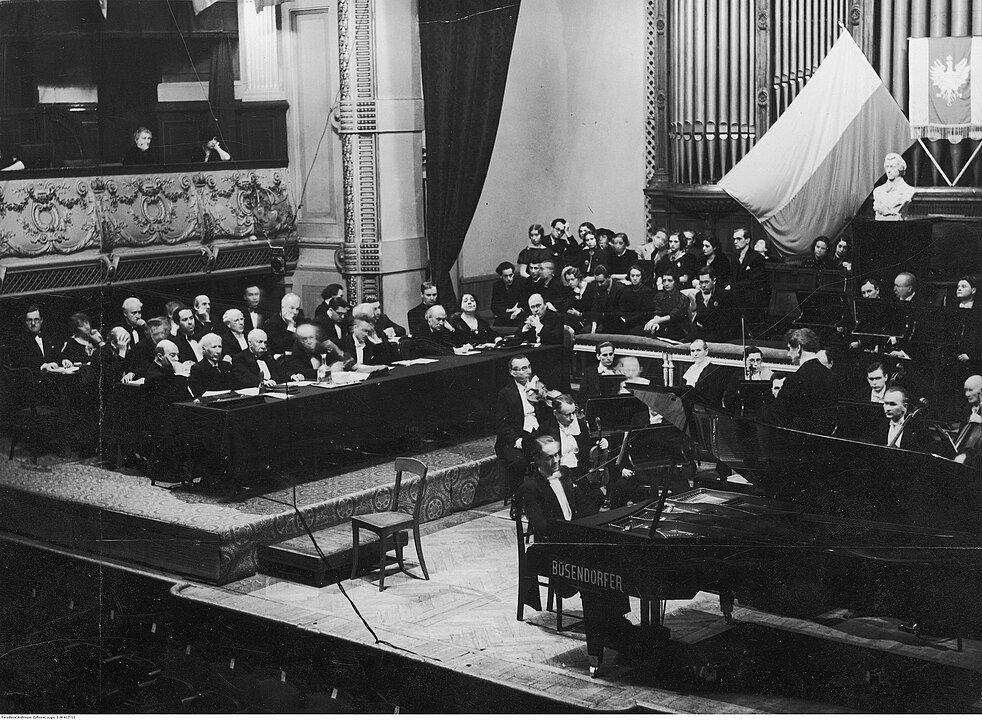

Image:

A Knowledge Club: the Royal Society in London. Photo-credit: By Copyright Kaihsu Tai – Copyright Kaihsu Tai, CC BY 2.5. Source: Wikimedia Commons.