By Pier-Luc Dupont

While many institutions have recognised the arts’ potential contribution to intercultural dialogue, voter ethnocentrism or plain racism often make it arduous for policymakers to support foreign-origin artists and keep their own jobs. But what emerges when a social justice measure is brushed over in diplomatic hues? A surprising breakthrough may be the short answer.

The ideal of art for art’s sake has a long pedigree. ‘All art is quite useless’, famously quipped Oscar Wilde nearly 130 years ago in the preface of The Picture of Dorian Gray. However attractive to the disciples of romanticism and aesthetic experimentation, this notion has become increasingly unpopular in policy circles, where commodification (that is, art for the market’s sake) and instrumentalisation (or art for the sake of some other extrinsic goal) are quickly gaining ideological ground (Gray, 2007).

The instrumentalisation of cultural policy need not always be a cynical move. When it serves mental health, educational or social cohesion purposes, for instance, it may even be embraced by free-minded artists themselves. This being said, some of its manifestations are more clearly wedded to special interests. Authorities have thus been found to invest in culture with a view to increasing the prestige of local industries or real estate value in specific neighbourhoods (McGuigan, 2004; O’Brien, 2014).

Altruistic and selfish motives frequently blend together in policy formulation and publicising. One interesting case of overlap is the promotion of foreign artistic traditions through programmes which showcase artists from abroad or support local ones who identify with an migrant background. To the extent that they benefit negatively racialised creators, such measures may help neutralise White or Eurocentric biases in the artistic sphere, but they have also been sold to taxpayers as instances of public diplomacy serving foreign policy objectives. In the current climate of anti-immigrant hostility, it is therefore tempting to ask whether diplomatic framings could buttress morally necessary but electorally costly programmes to improve attitudes toward the stigmatised ‘others’.

To answer this question, I systematically compared the creation, functioning and predictable impact of two institutions supporting racialised artists: the Equity Office of the Canada Council for the Arts, self-described as an instrument for social justice, and the Spanish network of cultural Houses (Red de Casas), presented as a catalyst for political and economic cooperation. My analysis suggests that equity-oriented and diplomatically-tinged cultural policies have complementary strengths, even if the latter can hardly be cast as a perfect substitute for the former.

The first complementariness has to do with timing. Whereas the Equity Office was set up after a consultation on systemic racism in the Canada Council for the Arts, itself preceded by the constitutional and legislative protection of multiculturalism, the oldest House appeared 15 years before the adoption a comprehensive integration strategy in Spain. Hence, diplomatic measures can be implemented independently from the high-level endorsement of cultural diversity.

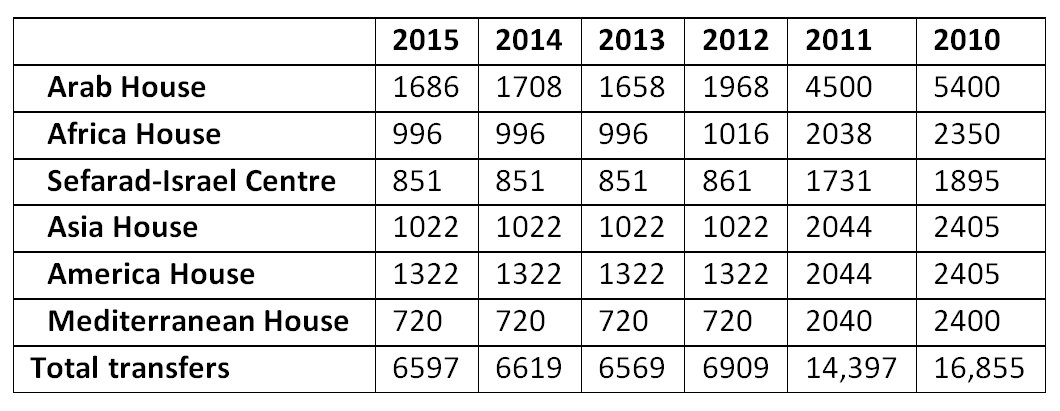

They also seem able to attract higher overall funding from governments and other deep-pocketed stakeholders. In 2013-2014, the Equity Office distributed approximately 1% of Arts Council grants to artists and cultural organisations, but the resources lavished on Houses by the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2015 added up to 6% of Ministry of Culture grants. In addition, the Houses have lured foreign embassies and, in the case of those dealing with emerging markets in Asia and Latin America, Spanish multinationals. The price of their closer alignment with political winds has been greater exposure to electoral storms. While funding for the arm’s-length-governed Equity Office barely rippled after the shift from a Liberal to a Conservative government in 2006, the Houses had to weather a 50% fall in subsidies when the centre-right Popular Party took over from the Socialists in 2011 (most local-level support dried out). The harshest cuts targeted Arab House, launched in the wake of the UN-led Alliance of Civilization jointly sponsored by Spain and Turkey to improve relations between ‘Western’ and ‘Islamic’ societies (see Table 1).

Table 1: Foreign Ministry transfers to the Houses (in thousand €).

Source: Government of Spain, annual budgets.

Other convenient contrasts include equity policies’ tendency to benefit small non-profits, seemingly designed to make up for diplomatic institutions’ propensity to team up with established editors, film producers, labels, festivals and so on. In the Spanish case they even grew into self-standing cultural centres, headquartered in refurbished historical buildings and equipped with high-tech facilities. Finally, the Equity Office exclusively supports Canadian residents, who are able to convey personal experiences of settlement in the local community, whereas the Houses also boost the visibility of foreign artists, who may be seen as more representative of future migrants’ societies of origin.

Despite all the virtues of public diplomacy as a driver of anti-racist cultural policies, we should beware of entirely replacing moral frames with strategic ones. The most obvious reason is that eliminating racism is a fundamental aim in its own right. Surely it would be reckless to subordinate it to contingent political alliances or international trade. Building racial justice with diplomatic tools may also yield wobbly foundations and leaky rooves. Compared to the Equity Office, the Houses thus pay little attention to artists’ (dis)abilities, gender, sexual orientation and class, as well as to peer assessments of aesthetic merit. The heyday of art for art’s sake may have passed, but it is hard to imagine cultural projects getting very far without some ideal of beauty to guide them.

References

Gray, C. (2007), ‘Commodification and instrumentality in cultural policy’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13:2, pp. 203–15.

McGuigan, J. (2004), Rethinking cultural policy, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

O’Brien, D. (2014), Cultural policy: Management, value and modernity in the cultural industries, Abingdon: Routledge.

The article is based on:

Dupont, P.-L., The inclusion of non-Western artistic traditions in cultural policy: Contrasting social justice and public diplomacy approaches, Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture, Volume 8, Number 1, 1 April 2017, pp. 49-65(17).

About the author:

Pier-Luc Dupont is Research Associate at the University of Bristol School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, within the Horizon 2020 project ETHOS – Toward a European Theory of Justice and Fairness. He holds a PhD in Human Rights, Democracy and International Justice from the University of Valencia.

Image source:

Palacio de Linares, https://www.linares28.es/2011/03/15/el-madrid-de-los-murga-por-carmen-maceiras-rey/