By Carmen Camarero, Maria José Garrido, and Eva Vicente

In the current health and economic crisis triggered by Covid-19, the future of museums is facing a major financial challenge, a challenge that has appeared when the echoes of the previous crisis are still ringing. Indeed, this crisis has reopened the debate over museum funding.

The financial crisis of 2008 led to substantial cutbacks in public contributions to cultural organizations. Indeed, the cuts in public funding had already started years before, coupled with a shift in cultural policies that demanded greater self-financing of museums so as to stimulate innovation, coupled with more efficient management. This led to an increased focus on fundraising through donations and sponsorship, or the privatization of certain services, both in museums that already had a more business-like tradition, as well as in those displaying a more public tradition. However, museums that depend too much on private funding or too much on public funding have greater difficulty innovating than those that have access to both1.

Now, the Covid-19 crisis has forced museums, first, to close and, then, to reduce the number of visitors. According to the NEMO report on the impact of COVID-19 on museums in Europa, museums in touristic regions reported income losses of 75-80%. The impact on their income has been on such a scale that, even museums whose profits came from their own income, consider it urgent to change their strategy and to seek national or international private financing. In this critical situation, as it is recommended by NEMO report, public funds should not ignore the cultural sector, although at the same time museums could increase their efforts to secure private funding.

Currently, we are studying the factors that determine the museums ability to attract and maintain sponsors and donors2. Interviews held with some museum directors indicate that museums’ capability to attract private funding is related to the signals and image they convey. We highlight some of these signals:

Fundable projects. A signal to attract donors and sponsors is to offer them flexibility as well as a range of potential projects that are of interest to both parties. Museums report that the most lasting collaborations are based on joint projects. This is the way to achieve the museum-sponsor association and to share the project’s result and success. This is why it is essential to find specific sponsors for specific projects and to decide which investments fit companies’ budgets and contribute to their visibility: in short, to find the right content for each company.

Reputation. Brand image is one of the main attractions for sponsors. The museum’s image can be linked to the museum itself, its collection, the number of visitors, or even the prestige of the city in which it is located. The museum’s prestige is key to attracting sponsors and to achieving receptivity in the projects proposed. In this sense, small museums and those that are not familiar or are less visible, may strive to create brand image and emphasize the benefits for sponsors of collaborating with them.

Social performance. Companies will be more willing to collaborate in projects that highlight the cultural value and social benefits which museums provide: legacy, prestige, educational value, or revenue and employment in local economies. Companies are usually more receptive to projects related to education and cultural dissemination. In this sense, the consumption of culture through different means (content platforms, social networks) has been enormous during the crisis. These behaviours are likely to persist and museums should be prepared to reach the public and fulfil their social function through both traditional channels as well as through new distribution formats.

Accountability. This refers to the museum’s effort to become transparent towards donors, sponsors, public authorities, and society as a whole. If museums are transparent, show their accounts as well as the objectives their investments pursue, companies are more likely to collaborate.

Relationships with local institutions. Maintaining close relationships with companies and institutions located in the same town can prove essential for museums’ financing. It is about showing yourself as a museum linked to your city and its surroundings, and thus getting the support of local companies and social media.

From local to international sponsors. In addition to being linked to the local society, museum directors recognise that overseas projection must not be overlooked because museums can offer added value to international companies, in terms of potential foreign visitors, awareness of foreign brands, etc. This requires a wide range of collaboration possibilities where different types of trustees and corporate members have a place.

Flexibility of public-private collaboration. Finally, we need to highlight the problems that public museums face when collaborating with private firms. Collaboration projects are extended and may fail because of the complicated administrative procedures they require (agreements, permits, authorization, intermediary foundations to channel funding, etc.). Yet, public museums face huge difficulties when it comes to organizational change and running a museum with a business-like approach. In this sense, patronage and sponsorship laws are needed to facilitate the cooperation of public museums with companies and to make access to and management of funding more flexible.

1 Camarero, C., Garrido, M. J., & Vicente, E. (2011). How cultural organizations’ size and funding influence innovation and performance: the case of museums. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(4), 247.

2 Project Management of relationships with customers and other stakeholders: strategies, tools and results. Project reference: VA219P20. Junta de Castilla y León (Spain). Grants from the programme to support research projects co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund. 2021-2023.

This article is based on:

Camarero, C., Garrido, M.J. & Vicente, E. How cultural organizations’ size and funding influence innovation and performance: the case of museums. J Cult Econ 35, 247 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-011-9144-4

Project Management of relationships with customers and other stakeholders: strategies, tools and results. Project reference: VA219P20. Junta de Castilla y León (Spain). Grants from the programme to support research projects co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund. 2021-2023.

About the Authors:

Carmen Camarero is professor of Marketing at the University of Valladolid, Spain.

Maria José Garrido is associate professor of Marketing at the University of Valladolid, Spain.

Eva Vicente is associate professor of Applied Economics at the University of Valladolid, Spain.

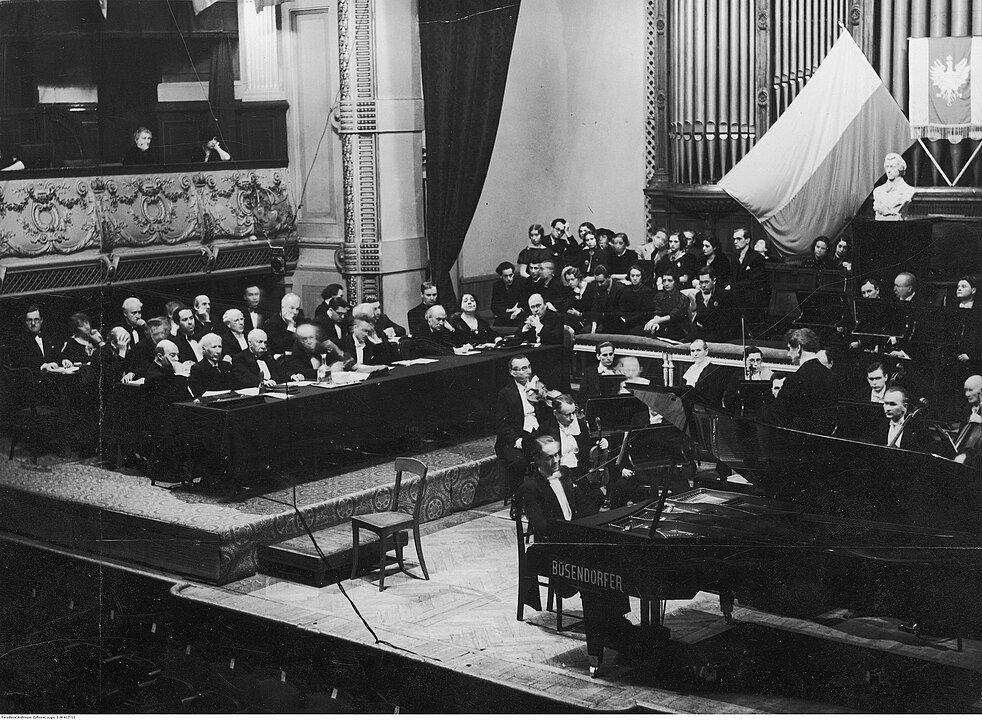

About the image: FouPic (2014) Interior del Museo del Prado.