The great Italian sculptor Michelangelo has allegedly once said, “Every block of stone has a statue inside, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” We have always believed that only humans held the incredible skill of imagining and creating art, as if it represented a form of self-expression unique to our own specie. However, this perspective has changed.

Throughout history, humans have permanently pursued to optimize processes and solve problems more efficiently. The main thread that connects our changes from hunter-gatherers to the agricultural revolution, to the industrial revolution, to the digital, and now the autonomous era, is the arrival of new technologies to solve existing problems. Along this process the solutions became more sophisticated, from bow and arrows to irrigation systems, factory machines, software, and, lastly, automation. Yet, the premises and first attempts of the automation of processes through “intelligent technologies” have started many decades ago.

In 1950, Allan Touring suggested the touring test, also known as the imitation game. In 1951 Christopher Strachey developed the first “AI” machine able to play a complete game of draughts (checkers). However, the term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined five years later by John McCarthy who initiated the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence with the collaboration of Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon.

AI and Music Composition

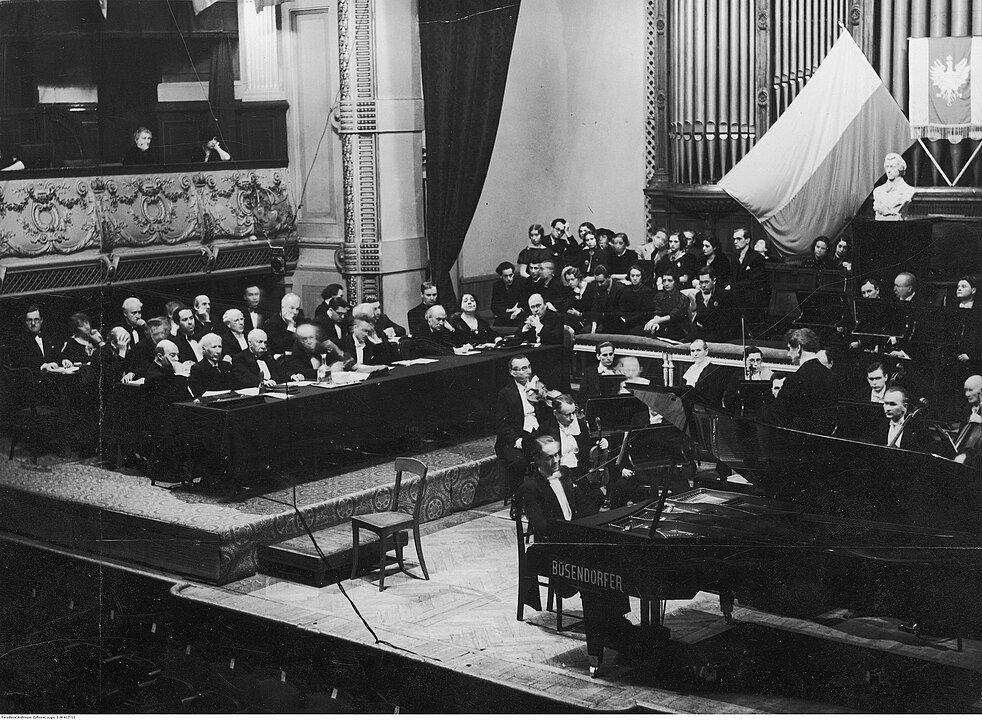

In 1951, Christopher Strachey was the first to program a computer to perform music; a rendition of God Save the Queen. But music is connected to mathematics in a much more fundamental way. Indeed, behind every song or melody, there is a mathematical reasoning. The Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras discovered the mathematical relationship of tones and ratios in music and sound waves, and set the basis for music theory and harmony in western countries. No wonder Pythagoras is often called the “father of numbers,” but also the “father of harmony.” But what does AI have to do with harmony? Well, one of the most suitable tasks for artificial intelligence is to analyze extremely large amounts of data and identify patterns. Given the mathematical basis of music theory, AI can also be used for music analysis and composition.

In 1977, composer David Cope started working at the University of California but a few years later he faced a writer’s block. Despite the professional pressure, he sought an innovative solution. He combined his knowledge of music theory and programming to create what later became EMI: Experiments in Musical Intelligence. In a nutshell, EMI was a tool that composed music through three essential steps: First, “Deconstruction”: analyzing music compositions and separating them into parts. Second, “Signatures”: Identifying commonalities, which signifies and characterizes a style of a genre or composer. Lastly, “Compatibility”: recombining pieces, patterns and styles to create new original works. Through this process, EMI composed thousands of songs.

Decades after EMI, software and hardware improved greatly. As a consequence, multiple companies have developed AI based solutions for music composition, such as AIVA, Jukedeck, Humtap, Endel, Amper, Brain.FM, Melodrive and Popgun. All these tools have helped musicians, composers, and producers to co-create music with AI.

How do music listeners react to music composed by Artificial Intelligence?

My research shows that, in general, the perception towards using artificial intelligence to compose music is rather negative. Listeners seem to admire the ability of artists to express sincere human emotions through songs. However, during an experiment, we manipulated the description of how the songs had been composed. For one group, we told them a fictitious story about the emotional reasoning behind the composition. For another group, we told them AI had autonomously composed it.

The main finding is that the use of AI during the composition process had no effect on listeners as long as they enjoyed what they heard. This finding is actually not as surprising as it may seem. Although one may not appreciate the process through which an artistic output has been created, it is challenging to react negatively if a song triggers on us an (involuntary) positive emotional response.

What does the future hold?

We must expect an exponential increase of music composed with AI. Whether for meditation, music therapy, soundtracks, gaming, jingles or for pure hedonistic enjoyment, AI will be used in recording studios. Why? It facilitates processes and provides an extraordinary economy of scale.

The challenge is that it will be difficult to judge the intention and ability of artists. Audiences will be left guessing. Once a song or album is released, they will have to rely solely on the artists’ word to know if the track is an honest human expression of emotion and technical ability, or if it was co-created with AI or autonomously generated.

For me, a fan of “organic music” and artists such as The Beatles and Bob Dylan, this represents an immense loss. But for a new generation, born during the autonomous era, artificially composed or co-created music might simply represent a new form of creativity.

I just hope that, in the coming years, there will still be others like me interested in listening to songs that someone composed alone in a bedroom, with an instrument, during a moment of sadness or joy.

After all, at least so far, algorithms cannot feel emotions.

This article is based on:

Tigre Moura, F. and Maw, C. (2021), “Artificial intelligence became Beethoven: how do listeners and music professionals perceive artificially composed music?”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 38 No. 2, pp. 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2020-3671

About the author:

Francisco Tigre Moura is a Professor of Marketing at IU University of Applied Sciences, in Bad Honnef (Germany), and writer at LiveInnovation.org.